Facebook paid a cybersecurity firm six figures to develop a zero-day in a Tor-reliant operating system in order to unmask a man who spent years sextorting hundreds of young girls, threatening to shoot or blow up their schools if they didn’t comply, Motherboard’s Vice has learned.

We already knew from court documents that the FBI tricked the man into opening a booby-trapped video – purportedly of child sexual abuse, though it held no such thing – that exposed his IP address. What we didn’t know until now is that the exploit was custom-crafted at Facebook’s behest and at its expense.

Facebook had skin in this game. The predator, a Californian by the name of Buster Hernandez, used the platform and its messaging apps as his hunting grounds for years before he was caught.

Hernandez was such a persistent threat, and he was so good at hiding his real identity, that Facebook took the “unprecedented” step of working with a third-party firm to develop an exploit, Vice reports. According to the publication’s sources within Facebook, it was “the first and only time” that Facebook has helped law enforcement hack a target.

It’s an ethically thorny discovery. On one hand, we’ve got the deeply troubling implications of Facebook paying for a company to drill a hole into a privacy-protecting technology so as to strip away the anonymity of a user – this, coming from a platform that’s promised to slather end-to-end encryption across all of its messaging apps.

On the other hand, it’s easy to cheer for the results, given the nature of the target.

Arrested in 2017 at the age of 26, Hernandez went by the name Brian Kil (among 14 other aliases) online. Between 2012 and 2017, he terrorized children, threatening to murder, rape, kidnap, or otherwise brutalize them if they didn’t send nude images, encouraging some of them to kill themselves and threatening mass shootings at their schools or a mall bombing. In February 2020, he pleaded guilty to 41 counts of terrorizing girls aged 12 to 15.

Although Facebook reportedly hired an unnamed third-party to come up with a zero day that would lead to the discovery of Hernandez’s IP address and eventual arrest, it didn’t actually hand that exploit over to the FBI. It’s not even clear that the FBI knew that Facebook was behind the development of the zero day.

The FBI has, of course, done the same thing itself. One case was the Playpen takedown, when the bureau infamously took over a worldwide child exploitation enterprise and ran it for 13 days, planting a so-called network investigative technique (NIT) – what’s also known as police malware – onto the computers of those who visited.

In the hunt for Hernandez, a zero-day exploit was developed to target a privacy-focused operating system called Tails. Also known as the Amnesic Incognito Live System, Tails routes all incoming and outgoing connections through the Tor anonymity network, masking users’ real IP addresses and, hence, their identities and locations. The Tails zero-day was used to strip away the anonymizing layers of Tor to get at Hernandez’s real IP address, which ultimately led to his arrest.

Facebook: We had no choice

A Facebook spokesperson told Motherboard that the publication got it right: the platform had indeed worked with security experts to help the FBI hack Hernandez. The spokesperson provided this statement:

The only acceptable outcome to us was Buster Hernandez facing accountability for his abuse of young girls. This was a unique case, because he was using such sophisticated methods to hide his identity, that we took the extraordinary steps of working with security experts to help the FBI bring him to justice.

A former Facebook employee with knowledge of the case said that this was an extremely targeted hit that didn’t affect other users’ privacy:

In this case, there was absolutely no risk to users other than this one person for which there was much more than probable cause. We never would have made a change that affected anybody else, like an encryption backdoor.

Since there were no other privacy risks, and the human impact was so large, I don’t feel like we had another choice.

The human impact was not only large: it was vicious and unrelenting. Hernandez lied to victims about having explicit images of them and demanded more, lest he send photos to their friends and family. He did, in fact, publish some victims’ intimate imagery. For one victim – identified as Victim 1 in the criminal complaint – he doctored videos she’d taken of herself dancing. She thought she’d deleted them, Hernandez said in one of his many braggart’s posts. He got the videos anyway, he said, having hacked her cloud account to get the imagery, which he edited to appear explicit.

He lied about having weapons, he lied about plans to shoot up a high school, he lied about a bomb at a mall. His rape threats were long and graphic, describing how he’d slit girls’ throats or kill their families. Sometimes, he encouraged his victims to kill themselves. If they did, he’d post their nude photos on memorial pages, he said.

In December 2015, multiple high schools and shops in the towns of Plainville and Danville, Indiana, were shut down due to Kil’s terrorist threats. The following month, the community, along with police, held a forum to discuss the threats.

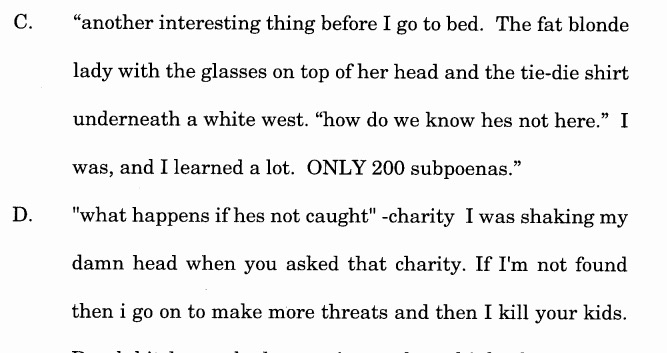

After the forum, Kil posted notes about who attended, what they wore, and what was said, as reported to him by a victim whom he’d coerced into attending and reporting back to him.

(IMAGE: Criminal complaint)

What he wrote in 2015, after telling victims he “wants to be the worst cyberterrorist who ever lived”:

I want to leave a trail of death and fire [at your high school]. I will simply WALK RIGHT IN UNDETECTED TOMORROW … I will slaughter your entire class and save you for last. I will lean over you as you scream and cry and beg for mercy before I slit your f**king throat from ear to ear.

Not all Facebook employees agreed

Several employees, both current and former, told Vice that the decision to hack Brian Kil was more controversial than the company’s statement would indicate. You can see why they’d have qualms: the same operating system that hid Hernandez for years as he contacted and harassed hundreds of victims is also widely used by those whose work – or whose very lives – depend on the privacy and anonymity of Tor, including journalists, dissidents, activists and survivors of domestic abuse.

A spokesperson for Tails told Vice that the operating system is used daily by more than 30,000 such people, all of whom seek the shelter of Tor to avoid persecution, surveillance and/or the chance of falling back into the hands of their abusers. The flaw that was exploited in order to catch Hernandez – found in Tails’ video player to reveal the real IP address of the person viewing a video – was never disclosed to Tails. If the flaw hadn’t been done away with in a patch, it could have been used against innocent people.

Besides protecting monsters like Hernandez, anonymizing technologies such as Tails, Tor and encryption protect the privacy of others who deserve products that don’t have holes drilled into them. That’s why we and other encryption supporters have always pledged our support for #NoBackdoors.

But what does a company like Facebook do when it feels it has no other choice but to penetrate Tor in order to stop a menace to society?

Coming to the aid of the FBI

Both the FBI and Facebook were trying to get Hernandez. He was considered public enemy No. 1 at Facebook, which took extraordinary measures to track what employees considered to be the worst criminal to ever use the platform.

The company dedicated one employee to tracking Hernandez for two years. Hernandez’s reign of terror also inspired the platform to develop a new machine learning system: one that could detect users who create new accounts that they use to reach out to kids in order to exploit them. According to former employees, that system detected Hernandez and tied him to a number of pseudonymous accounts and their victims.

The FBI tried to hack Hernandez. But it didn’t go after him by exploiting Tails, and its attempts failed. Hernandez detected the attempt and ridiculed the bureau over it. It was at that point that Facebook decided to help.

Facebook engineers and security researchers felt they had no choice. Others aren’t so sure. Vice referred to a statement from Senator Ron Wyden that questioned the lack of transparency in how law enforcement handles vulnerabilities. From that statement:

Did the FBI re-use [the zero day] in other cases? Did it share the vulnerability with other agencies? Did it submit the zero-day for review by the inter-agency Vulnerabilities Equity Process? It’s clear there needs to be much more sunlight on how the government uses hacking tools, and whether the rules in place provide adequate guardrails.

Some Facebook employees agree: if this is a precedent, it’s not a good one. Vice quoted one such:

The precedent of a private company buying a zero-day to go after a criminal. That entire concept is f**ked up.

It is f**ked up. Ethically, it’s about as problematic as you can get. But, understandably, what Facebook pulled off is also a great source of pride to the engineers who worked on getting this guy, such as this former employee:

I think they totally did the right thing here. They put a lot of effort into child safety. It’s hard to think of another company spending the amount of time and resources to try to limit damage caused by one evil guy.